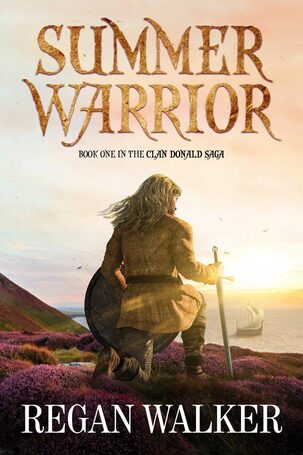

Excerpt for Summer Warrior

The Village of Drimnin, Morvern, Argyll, late summer 1136 A.D.

SOMERLED SMELLED THE SMOKE before he reached the village.

A small community nestled around a crescent bay on the western shore of Morvern, everyone who lived in Drimnin was related either by blood or marriage. The villagers made a good life raising cattle and reaping the bounty of the sea. Somerled had passed this way only once, and then he had approached from the Sound of Mull in his galley. He remembered the villagers’ humble but generous hospitality.

Today, he and his men had traveled on foot along the coast, wending their way through the pine woods in search of the Norse rumored to be raiding the shores of Morvern, hoping to catch them before they could strike. His ships were still too few to take them on the water.

He stepped out of the trees, lush with ferns at their base, his hand on his sword hilt, prepared to fight.

A ghastly sight met his eyes, sickening his stomach.

Too late.

Bodies were sprawled upon the grass between the shore and the woods, struck down while trying to flee. Dreadful wounds revealed some had fallen to axes.

Acrid smoke rose from the cottages still burning, the flames leaping from the dry thatched roofs. He could see no longships pulled up on shore but the raiders could not have been long gone.

Aghast at what he saw, he was suddenly aware there were no birds to be heard, save the hooded crows pecking at the blood-soaked bodies. “See if any live,” he said to Domnall and started forward.

“Aye,” said his cousin and swung his arm in silent command, pointing to the fallen. The men hastened to obey.

Both old and young had been killed by the merciless Norse. Seeing the women who had been violated, Somerled ground his teeth. Their tunics had been ripped from their bruised bodies before they were killed. “Cover them,” he said to one of his men. “Cover them all with whatever you can.” The men closest to him hurried to accomplish the task.

He walked through the village, assessing the carnage. The doors of the burning cottages stood open. Goods, taken in haste, had been discarded like so much rubbish. So, too, had the Norse raiders considered the lives of the people. He knew they would see judgment in the next life but Somerled wanted justice in this life. He did not hate the Norse. How could he when his mother was one of them? But these were lesser men, ruthless pirates, some ostracized from their own people to prey on others.

When his men returned with reports that none lived, Somerled faced the woods and in Gaelic said in a gentle voice, “If you live, come to us or make a sound. We will help you.”

Two boys staggered out of the woods, their fearful expressions and tear-stained cheeks bearing witness to what they had seen. From the look of them, they were brothers, close in age, both with dark brown hair and wide eyes. To them, Somerled’s sun-gilded fair hair would mark him more Norse than Gael.

Kneeling before them, he said, “I am Somerled, a man of Argyll, and these are my men. You will be safe with us.” When he saw relief on their faces, he said, “We will return to bury the dead but now we must go in haste to exact vengeance on those who did this. Do you come with us?”

The boys shared a glance and the older one nodded. “We will come.” Somerled gave them into the care of a MacInnes man who stepped forward and offered to raise the boys with his own children. As they started to go, the older one said, “They took our sister and another girl.” It was clear from the boy’s haunted eyes he had an idea of the girls’ fate. Likely he had already witnessed the rape of the village women, including his own mother.

Somerled’s eyes narrowed as his heart hardened within his chest. “We will see them avenged.”

A short way down the coast, one of Somerled’s men scouting ahead had spotted dragonships offshore.

They approached the top of the rise and Somerled signaled his men to stay low. A field of yellow wildflowers bloomed where he crouched behind a boulder, observing the Norse longships. He counted five, three just pulling up at the water’s edge, their sails doused, their dragon-carved stems boding ill for the people who lived farther down the coast. Counting shields, he saw they numbered nearly three hundred.

The sea was calm, as if nature herself was unaware a massacre had just taken place to the north. Somerled’s heart burned within him, a furnace of rage. He wanted the waters to roar, to cry for vengeance on the heathen dogs.

Behind him were the forests in which he had hunted. Gathered around him was his group of one hundred men, MacInneses from Morvern, archers from Argyll and Irish mercenaries from Antrim, who had heard of his plan to retake Argyll and joined the cause. They were stout-hearted men yet still too few to take on so many Norsemen clad in mail and conical helms and armed with swords, axes and spears.

The Highlanders and Islesmen wore tunics of linen or wool over tight-fitting trews or hosen, their tunics secured at their waists with a belt. On their feet were soft leather boots. Around their shoulders, some wore woolen cloaks. A few, like Somerled and his brother, also wore leather armor. None wore mail. It was expensive and rare in these parts. All carried weapons but not all had a steel sword at their waist.

No matter the odds against them, Somerled wanted those ships and he wanted justice for the lives cut short at Drimnin.

Copyright © 2020 Regan Walker

SOMERLED SMELLED THE SMOKE before he reached the village.

A small community nestled around a crescent bay on the western shore of Morvern, everyone who lived in Drimnin was related either by blood or marriage. The villagers made a good life raising cattle and reaping the bounty of the sea. Somerled had passed this way only once, and then he had approached from the Sound of Mull in his galley. He remembered the villagers’ humble but generous hospitality.

Today, he and his men had traveled on foot along the coast, wending their way through the pine woods in search of the Norse rumored to be raiding the shores of Morvern, hoping to catch them before they could strike. His ships were still too few to take them on the water.

He stepped out of the trees, lush with ferns at their base, his hand on his sword hilt, prepared to fight.

A ghastly sight met his eyes, sickening his stomach.

Too late.

Bodies were sprawled upon the grass between the shore and the woods, struck down while trying to flee. Dreadful wounds revealed some had fallen to axes.

Acrid smoke rose from the cottages still burning, the flames leaping from the dry thatched roofs. He could see no longships pulled up on shore but the raiders could not have been long gone.

Aghast at what he saw, he was suddenly aware there were no birds to be heard, save the hooded crows pecking at the blood-soaked bodies. “See if any live,” he said to Domnall and started forward.

“Aye,” said his cousin and swung his arm in silent command, pointing to the fallen. The men hastened to obey.

Both old and young had been killed by the merciless Norse. Seeing the women who had been violated, Somerled ground his teeth. Their tunics had been ripped from their bruised bodies before they were killed. “Cover them,” he said to one of his men. “Cover them all with whatever you can.” The men closest to him hurried to accomplish the task.

He walked through the village, assessing the carnage. The doors of the burning cottages stood open. Goods, taken in haste, had been discarded like so much rubbish. So, too, had the Norse raiders considered the lives of the people. He knew they would see judgment in the next life but Somerled wanted justice in this life. He did not hate the Norse. How could he when his mother was one of them? But these were lesser men, ruthless pirates, some ostracized from their own people to prey on others.

When his men returned with reports that none lived, Somerled faced the woods and in Gaelic said in a gentle voice, “If you live, come to us or make a sound. We will help you.”

Two boys staggered out of the woods, their fearful expressions and tear-stained cheeks bearing witness to what they had seen. From the look of them, they were brothers, close in age, both with dark brown hair and wide eyes. To them, Somerled’s sun-gilded fair hair would mark him more Norse than Gael.

Kneeling before them, he said, “I am Somerled, a man of Argyll, and these are my men. You will be safe with us.” When he saw relief on their faces, he said, “We will return to bury the dead but now we must go in haste to exact vengeance on those who did this. Do you come with us?”

The boys shared a glance and the older one nodded. “We will come.” Somerled gave them into the care of a MacInnes man who stepped forward and offered to raise the boys with his own children. As they started to go, the older one said, “They took our sister and another girl.” It was clear from the boy’s haunted eyes he had an idea of the girls’ fate. Likely he had already witnessed the rape of the village women, including his own mother.

Somerled’s eyes narrowed as his heart hardened within his chest. “We will see them avenged.”

A short way down the coast, one of Somerled’s men scouting ahead had spotted dragonships offshore.

They approached the top of the rise and Somerled signaled his men to stay low. A field of yellow wildflowers bloomed where he crouched behind a boulder, observing the Norse longships. He counted five, three just pulling up at the water’s edge, their sails doused, their dragon-carved stems boding ill for the people who lived farther down the coast. Counting shields, he saw they numbered nearly three hundred.

The sea was calm, as if nature herself was unaware a massacre had just taken place to the north. Somerled’s heart burned within him, a furnace of rage. He wanted the waters to roar, to cry for vengeance on the heathen dogs.

Behind him were the forests in which he had hunted. Gathered around him was his group of one hundred men, MacInneses from Morvern, archers from Argyll and Irish mercenaries from Antrim, who had heard of his plan to retake Argyll and joined the cause. They were stout-hearted men yet still too few to take on so many Norsemen clad in mail and conical helms and armed with swords, axes and spears.

The Highlanders and Islesmen wore tunics of linen or wool over tight-fitting trews or hosen, their tunics secured at their waists with a belt. On their feet were soft leather boots. Around their shoulders, some wore woolen cloaks. A few, like Somerled and his brother, also wore leather armor. None wore mail. It was expensive and rare in these parts. All carried weapons but not all had a steel sword at their waist.

No matter the odds against them, Somerled wanted those ships and he wanted justice for the lives cut short at Drimnin.

Copyright © 2020 Regan Walker